Most view innovation a big bang type of exercise – or an “aha” moment that came out of nowhere. Indeed, cogito ergo sum – an invention akin to “out nothing, something”. A look back in history will tell us that this notion is completely false.

In fact, looking at the components of the iPhone, you’ll see that the apple iphone components were not invented or created from nothing – they’re in fact plain vanilla components used for other devices:

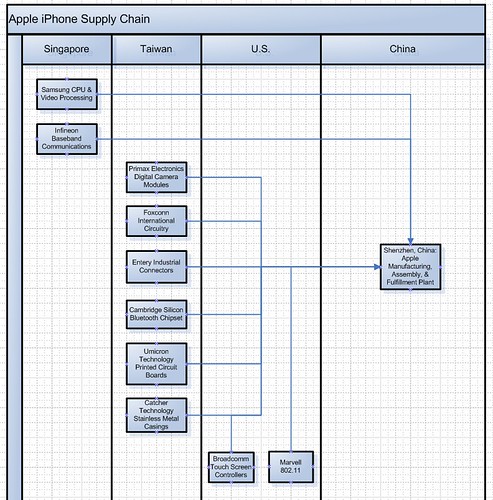

- Samsung: The Singapore facility manufactures CPU and Video processing chips.

- Infineon: The Singapore facility manufactures Baseband Communications hardware.

- Primax Electronics: The Taiwan facility manufactures Digital Camera Modules.

- Foxconn International: The Taiwan facility manufactures internal circuitry.

- Entery Industrial: The Taiwan facility manufactures connectors.

- Cambridge Silicon: The Taiwan facility manufactures bluetooth chipsets.

- Umicron Technology: The Taiwan facility manufactures printed circuit boards.

- Catcher Technology: The Taiwan facility manufactures stainless metal casings.

- Broadcomm: The U.S. based facility builds touch screen controllers.

- Marvell: The U.S. based facility builds 802.11 specific parts.

The Apple Shenzhen, China facility assembles the hardware, holds inventory, and handles the pick, pack, and ship steps of the fulfillment process.

But, this type of thinking breeds another type of thinking that I’d like to address: Solutions in Search of a Problem

Solution in Search of a Problem

In Lean Thinking, it’s clear that we must first understand the problem, it’s root causes, and then addressing each root cause appropriately with simple, effective countermeasures. But, this works effectively well when the symptoms are known and there is a problem that has been articulated.

But, what if the problem isn’t articulated? What if there is a problem, but it’s just difficult to put words to it. Or, what if there is a problem, but people don’t even know it’s a problem.

We Don’t Know What We Don’t Know

Take, for example, the Proctor & Gamble Swiffer mop vacuum. In that situation, a cross-functional team of IDEO and P&G team members observed stay-at-home moms actually mopping their floors. What they observed was fascinating:

They were spending more time cleaning their mops than cleaning the floor

This observation led to the invention of the Swiffer Mop.

Here was clearly a situation where

there was a problem – but, people didn’t know it was a problem.

The Swiffer example is a situation where a solution was created to solve an unarticulated problem. This is clearly different from creating a solution when there is no problem to be solved.

In Lean Thinking, the approach that IDEO took is what is practiced as Genchi Genbutsu. It’s principles come from the science of ethnography.

A Wants Versus Needs Matrix

A wants-needs matrix to make your decisions is sometimes not helpful – especially since we know that some needs we don’t even know. For example,

| Need | Don’t Need | |

| Want | Food | iPad |

| Don’t Want | Exercise | Taxes |

Consciously, I might say I don’t need an iPad. But, after using one for several days, perhaps I couldn’t imagine my life without one.

Semi-Conclusion

Most true innovations are innovative because they solve a problem. The nature of those problems are what get complicated because there are some problems that we don’t even recognize are problems yet.

Be Done Now

The practice of “go and see” is critical. It’s an application of Ethnography and allows us to observe, empathize, and see what others may not see or recognize. Being able to see what others don’t see leads to innovation and in exposing unrecognized problems and solutions.

Become a Lean Six Sigma professional today!

Start your learning journey with Lean Six Sigma White Belt at NO COST

Jason Yip says

Just read something about technology companies that take a “solution looking for a problem approach” such as 3M and Dupont. There’s something about needing to understanding a solution space well enough to even know that a particular problem can be addressed.