Wired Magazine editor Chris Anderson’s new book The Long Tail is hot. It is a provocative and innovative book that attempts to show an economics that the web has created, where the sales of “non-hits” can cumulatively be larger than the sales of hot selling items. Essentially, the Longtail is a mathematical distribution that also explains the Pareto Principle. While his ideas are germane to many areas of business, such as the dessimination of information and, perhaps other areas as well, it has also wagged the tail of many “new economy”-type people and has inflated the personal bubbles of many web 2.0’ers. In what follows, I will respond to one of the main themes in the book, in which Anderson uses Amazon as one of the examples.

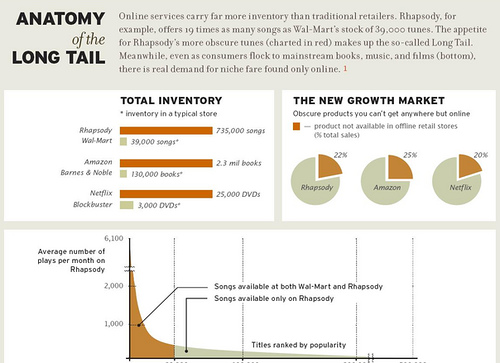

Anderson claims that products in low demand or have low sales volume can collectively make up a market share that rivals or exceeds the relatively few current bestsellers or ‘hits’. Put simply, the demand for the items in the Long Tail — both content and products — is getting bigger. But, in order to satisfy the Long Tail demand, the distribution channel has to be large and broad enough and overall fulfillment cost has to be low such that sales of Long Tail items is still profitable — cumulatively. In other words, as things move online, sales of misses will increase — so much so that they can equal or exceed sales of hits. Anderson emphasizes, however, that the cumulative effect of items in the tail and its equivalent sales percentage and absolute sales numbers might take time to be cumulatively larger than the head (“hits”). By “hits”, he is speaking about blockbusters or bestsellers or items with high demand.

Anderson uses forensic economics via a research team at MIT to conclude that the Amazon.com Book Category Tail is 57%. This claim was met with much response from the readership community and after some journalistic firefighting by Anderson, he decided to speak with Jeff Bezos who provided a rough swag at some numbers and suggested that 25% of Amazon’s book sales are from its tail. Below is his graphic to demonstate the decomposition of Hits vs Non-hits [source: page 5, ChangeThis.com, PDF File, The Long Tail]:

First, in all due respect to Jeff Bezos, whom I admire, was the wrong person to ask. The person that should’ve been asked was Jeff Wilke. Jeff Bezos is great, but he’s not that involved on the fulfillment and distribution side, which is also the side that cares about inventory and the breakdown of that inventory in the context of sales and revenue.

Moreover, if Anderson is going to use the work of MIT professors, he should have known that there are professors much more intimate with Amazon than Brynjolfsson, Hu, and Smith. Amazon has had a long, close partnership with the MIT-LFM program and I’ve personally worked with several professors from that program (and I managed a few interns from there as well) while I was at Amazon. But, even if Anderson contacted professors from the MIT-LFM program that in fact have a direct affiliation with Amazon, he might not have gotten much in terms of data or opinion due to Amazon’s intense secrecy. So, in all fairness to him, Anderson used the best data available.

Second, why use just books as the sample category? Was it because that was the best available data he had? If so, I understand and I concede that that approach is academically decent but insufficient. You see, Amazon does do analysis at the granular category level, but cares more about the level above that: Books, Movies, Videos, and DVD’s (BMVD‘s) and everything else as Hardlines.

When I left Amazon.com in 2005 after 3 amazing years, there were more BMVD’s than Hardlines, but Hardlines represented a higher percentage of sales and recognized revenue. In fact, there was a nice seperation of data, such that an 80/20 was not met, but it’s still a nice looking Pareto. If Anderson had a more reliable data source, perhaps he could have looked at the Amazon business this way, instead of just books. Looking at one category — books — provides an incomplete view of the Amazon business; it’s not a reliable sample and hence the results from that analysis are insufficient to use to extrapolate or support the long tail thesis.

From my experience, I can say that the tail of BMVD’s and Hardlines — both — represented less than 20% of worldwide sales and recognized revenue. Perhaps that number has increased since 2004.

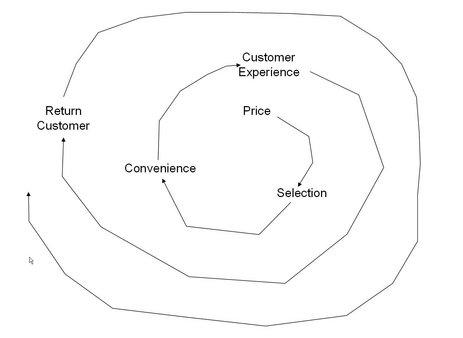

Anderson is correct in his analysis on Hit-driven Economics and the Economics of Abundance: the reason for the hard-to-find, non-blockbuster products at Amazon is to provide Selection for the customers. It’s difficult to predict what may or may not be in demand — current or future. A response to this fact is to stock some of everything. This only works if overall fulfillment cost can be minimized. In Operations, this approach is an Inventory Strategy for Multi-Echelon Systems. Internally, this approach and support for SELECTION has since been dubbed “Bezos’ Flywheel” and goes something like this:

[Price]->[Selection]->[Convenience]->[Customer Experience]->[Return Customer]->[…]. In other words,

The Flywheel analogy is meant to show that Price, Selection, and Convenience RESULT in a great Customer Experience and DRIVE Return Customers. Drawing is one of the things I do poorly, so my diagram above might not capture the point of the Flywheel. Please forgive me on that, but understand that Price, Selection, and Convenience RESULT in a great Customer Experience and DRIVE Return Customers.

So, in a way, Bezos’ motivation for providing Selection is almost benevolent: money is not really made on the non-hits, but by providing non-hits or an increased selection of niche items DRIVES a good Customer Experience and, Bezos is very focused on Customer Experience. But, while Selection supports demand, SALES are from items on the head, not the cumulative sum of the tail.

Anderson also explains, in a soft way, that low fulfillment and distribution costs make way for Long Tail businesses. He claims that this is why Amazon can provide such a large selection. Anderson doesn’t provide any numbers, however, to show that this is true. Are Amazon’s fulfillment and distribution costs low such that Selection is a supportable and profitable effort?

Well, fulfillment costs are getting lower. Amazon hires a lot of Operations Research, Optimization Experts, Six Sigma, Lean Manufacturing, and other Operations Experts to help drive cost our of Fulfillment and Operations. But, at least in 2004, fulfillment costs as a percentage of an average order was still in the order of 20% – 25% for both sortable and non-sortable orders. Sortable are items you can put on a conveyor; non-sortable are items too big for a conveyor. Non-sortable items can be referred to as full-case-non-conveyable also. That percentage used to be much higher, but Amazon — Jeff Wilke — especially, is relentless on driving costs out of Operations. I expect Fulfillment Costs to reach a floor, where no further marginal effort will reduce fulfillment costs. I don’t know what that number is, perhaps Amazon has already reached it.

One thing Amazon is doing to further reduce fulfillment costs while providing a Long Tail Selection is its entry into the on-demand printing business and on-demand video business. Last year, Amazon acquired BookSurge and CustomFlix so that warehousing costs for Long Tail items can be further reduced via on-demand printing of the non-hit items. This was a very smart move on Amazon’s part.

In conclusion, I don’t doubt the power of the web, nor do I wholly disagree with the Long Tail thesis. Anderson has written a very good book, whose ideas are germane to business and explain a phenomena that Google and Overture has capitalized on. My objection is around his use of Amazon as an example. Anderson uses books to support the Long Tail thesis; I argue that the use of Book data is insufficient. To Anderson’s credit, he recalibrates his estimate of Amazon’s Long Tail for Books by speaking with Jeff Bezos, but I argue that that number is still high, from my experience. Additionally, Anderson softly comments that minimizing Fulfillment and Distribution costs allows for Long Tail businesses to thrive. I agree, but to make that happen is not as easy as Anderson makes it out to be. There are many, many Ph.D’s, Operations Research, Lean Manufacturing, and Six Sigma folks in Amazon’s fulfillment arm to do exactly that — help reduce fulfillment costs and maintain a delightful fulfillment experience for the customer. It is difficult work and it takes many years of work and innovation to even arrive at the fulfillment costs that Amazon has arrived at. Nevertheless, Anderson’s book is relevant for our day, and I applaud his effort to explaining the Long Tail phonomena.

Shameless Plug — for more on shmula on Amazon, go here.

The Long Tail Debate Blogosphere

Foremski discusses where the profits are in the Long Tail

Lee Gomes questions Anderson’s Thesis

Gomes writes letter to Anderson

Business 2.0 asks “How long can the tail get?” — this is an unthoughtful question: for items that require physical space, the constraints are, well, space, labor, and process. For digital items, the corollary is similar, space for digital items is hardware and bandwidth. This question can only be asked by someone who does not have an Operations background. Business 2.0, I still dig you, but that question was a poor one.

BusinessWeek scrutinizes Anderson’s thesis; so does O’Reilly; so does Kazwell and Anderson comments

TexasVC puts the debate in perspective

BeyondVC blogs about the Long Tail

SeekingAlpha chimes in

It would be very interesting seeing the hard data that backs up this theory. Non-scientifically I can say that the tail is pretty big but 20% is probably a better estimate. I also agree that we should look at hardlines as well as books. We also might want to look at seasonality to see if the trend is different during the Christmas holiday.

The point you made about the work on optimising back end logistics via OR etc was very telling….reminds me that Amazon is still a physical distribution business at the end of the day, albeit with a good web front end….and that means physical limits to growth

with respect to the long tail……am I the only one seeing people seeming to cluster even more around the most popular stuff on social network content sites?