In general, Travel Time Sucks. Travel Time is Non Value Add. Lucky for us, Queueing Theory helps us put Travel Time in some perspective. You can also view all 40+ articles on Queueing Theory.

There are 3 types of activities, 2 of which produce waste:

- Steps that definitely create value.

- Steps that create no value, but are necessary given the current state of the system.

- Steps that create no value and can be eliminated.

(2) & (3) naturally create wastes, of which there are 7 types:

- Over-Production: Producing more than is needed, faster than needed or before needed.

- Wait-time: Idle time that occurs when co-dependent events are not synchronized.

- Transportation: Any material movement that does not directly support immediate production.

- Processing: Redundant effort (production or communication) which adds no value to a product or service.

- Inventory: Any supply in excess of process or demand requirements.

- Motion: Any movement of people which does not contribute added value to the product or service.

- Defect: Repair or rework of a product or service to fulfill customer requirements.

It’s important to understand “Value” in terms of the customer. From the custoemer’s perspective, “Value” could be defined in the form of a question:

Which process steps (and associated costs) do our customers not have to bear?

The answer to that question will define the non-value added steps that ought to be eliminated or reduced in order to bring more value to the customer.

Typically, value from the customer’s perspective is manifested in how long something takes to do. For example, at a restaurant, value is created when the right order is processed, delivered, and in a timely way. Time is critical in any service or hard-goods operation.

A Time-Study

Time-study analysis is common in industrial engineering. Conducting a time-study helps to reveal any waste or problems related to the service or product being used. Time-studies are used by industrial engineers, usability analyst, and also by ethnographers to learn about how people use products and how long it takes people to do something. The data gained from a time-study can be invaluable and can help the firm improve their product, service, or overall operation.

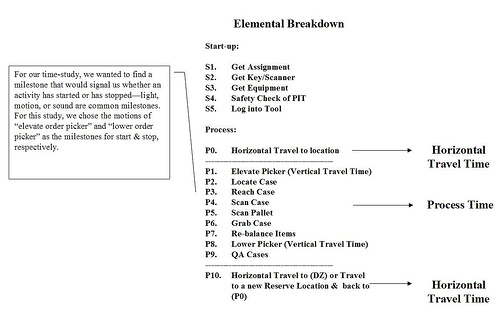

A while ago I was involved in a time-study. To begin, you want to identify elements or tasks, and then break those down into manageable pieces. For example, of an element takes less than 4 seconds to do, then you want to group that element with another one. Below is an example of a time-study for a warehousing process:

The above time-study has 4 major parts: the start-up, travel, process (locate, reach, grab, put), and travel again. My job was to time a random sample of people conducting this process, then analyze that data for any insights. Below is what we discovered during this process:

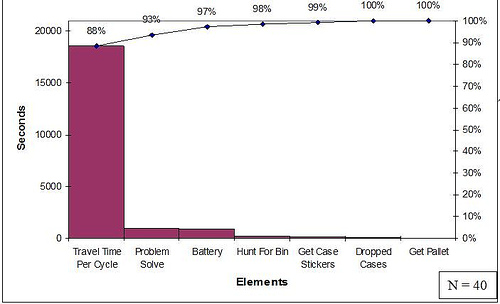

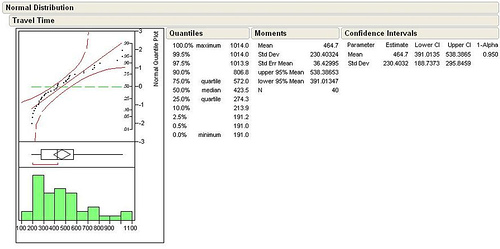

What initially began as a time-study, later became a discovery for waste — different types. I didn’t include the value-added time above, just the non-value added time. What the Pareto above shows is that travel time is the largest form of waste, but there are others also that can be eliminated. We also discovered that the travel-time was approximated by a normal distribution, which means we can employ the traditional tools that statistics offers us to see if there was an improvement in the process (t-test, chi-square, etc).

What we did for this project was to identify ways in which we can reduce travel time — travel time is a necessary, but we were able to reduce the travel time through some engineering of the location of bins, formation of the aisles, the size of the reserve area versus the picking (prime) area, and by switching to smaller batches per order. We also eliminated some of the other waste shown above and reduce the others.

Cost and Benefit Analysis

We calculated the travel time and associated waste to costs the firm about $230,000 per year (for this factory alone — there were 12 others with the same process). We took the projected hours spent in this process multiplied by the waste percentage (see Pareto above) multiplied by the average fully-burdened labor rate to arrive at a cost number. We eliminated 25% of the the waste and associated time-traps in this process, effectively saving ~$57,000. The cost to implement the improvements were trivial. No capital was purchased, just some simple, basic engineering — common-sense stuff was employed.

How This Relates to Queueing Theory

Eliminating waste reduces time that things are in process, allowing for other items to enter the queue. Reducing waste and time-traps helps the servers in the queue complete jobs and allows the jobs to exit the queue, freeing resources so that others can enter.

Conclusion

Travel time is necessary, but some of it can be reduced or completely eliminated. Travel time and some processing time are elements that customers would rather not pay for — it’s a burden that they shouldn’t have to carry in the form of higher prices or defects. We can be proactive in identifying waste in our processes — in any process — and employing process improvement to unlock the value-add that is in our business, resulting in a better customer experience, lower costs, and perhaps a more profitable business.

No responses / comments so far.